Neil Manthorp

History might well judge, and remember, one of the greatest cricketers of all time for an apparently inconsequential piece of jiggery-pokery performed almost a decade after his last match.

On the 21st July, 1994, South Africa started their first Test match at Lord’s a day short of 29 years after their last one at the ‘Home of Cricket.’ There were plenty of nerves but three members of the squad with the most experience of the venue, from County Cricket, rose valiantly to the occasion as the tourists won by an emphatic 356 runs.

Kepler Wessels scored 105, Allan Donald took 5-74 and Mike Procter smuggled the national flag into the ground to ensure it was flown prominently when victory was completed late on the fourth evening.

It’s easy to forget, 30 years later, that the new flag had been unveiled for the very first time less than three months earlier. Many white South Africans were still sceptical, if not scathing about the future. The flag represented confirmation that the future really was here to stay.

Regulations and ‘traditions’ at Lord’s can be painful and withering. It remains the only international cricket venue in the world where spectators can take their own bottles of wine, and glasses, so long as they dress ‘appropriately.’ The usual ban on flags, banners and placards had been enhanced in 1994 after a couple of old SA flags had been spotted in the stands on the first day. For once Lord’s got it right. A dozen or so unpleasant, bloody (and drunken) broken glass incidents were in order, but not the waving of an Apartheid flag.

“It’s the usual Lord’s bullshit,” muttered Proccie after being asked not to hang the new flag over the dressing balcony after day one. “There is no way this flag isn’t going to be seen by the world.” And so it was, removed from the railings after victory and handed to Krish Mackerdhuj and Ali Bacher to wave together after the win. An iconic image.

When it was suggested to him, in jest, much later that evening that he might be remembered more for defying the Lord’s regulations and kick-starting what was later to be termed ‘nation-building’ than anything he achieved on the field, he replied: “I bloody well hope so.” And those achievements were astonishing.

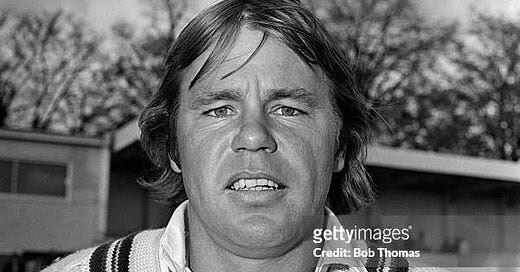

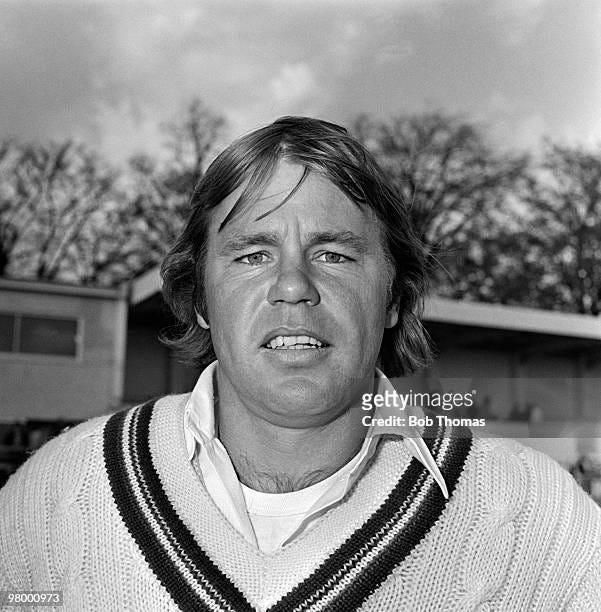

This tribute to the late, great Michael John Procter, who died on Saturday at the age of 77, was intended to be about the man rather than numbers. But suffice it to say that 1417 wickets at an average of 19.53 in 401 first-class matches, allied to 21,936 runs with 48 centuries, makes him the most productive all rounder in the history of the game.

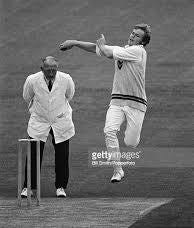

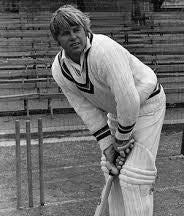

The debate about the standard and intensity of cricket in different eras which so often clouds comparisons of great players, never enters the conversation about Procter. He was unmatchable in his prime, awesome either side of it and still brilliant when bowling off-spin in his twilight playing years once the famously long run-up had finally taken its toll on his knees.

Barry Richards, ten months older, grew up with Procter in Durban and they played, for and against each other, for almost 60 years, two of the greatest cricketers of all time. Apartheid-induced isolation meant they played just four and seven Test matches respectively, but both ensured that history would record their potential should they have played more. A lot more. Richards scored 508 runs at 72 and Procter gathered up 41 wickets at a cost of just 15 runs each.

“He knew from an early age how different his pace and skill was,” said Richards, a day after his friend’s final departure. “Proccie was barely 20, bowling to Henry Fotheringham on his debut, batting at six. I was at the non-striker’s end. A nervous Fothers lunged forward at his first ball and missed it. Proccie said: ‘Oh, Larry the Lunger at six? This’ll be good…’ He brought square leg into short leg.

“Next ball was predictably short and Fothers lunged forward again before gloving it over short leg’s head to get off the mark. Proccie waited for him to shakily complete the run before saying, with a wide grin, “well played, I thought I had you there for a moment.” He could be venomous, but history recounts he never bit first. Batsmen quickly learned that Procter would play hard and fair – unless they didn’t.

He was appointed South Africa’s first coach upon their return to international cricket and oversaw a remarkable, unexpected run to the semi-final in the 1992 World Cup having been added to the tournament just a few months earlier. He was a ‘mentor’ more than a coach and the players loved him all the more for being so.

Later he became an ICC Match Referee and any hope for an ‘easy life’ was dogged by scandal, presiding over some of the game’s biggest controversies including Pakistan’s forfeiture of a Test match after ball-tampering accusations and India’s threat to abandon a Test series in Australia amidst allegations of racism. He handled it with public stoicism and private, careful amusement. He had seen too much in life to believe sports headlines would last longer than toilet paper. That may have been a quote. I can’t be sure.

He loved the camaraderie of the team and, like many career-players, sought to recreate that environment after his playing days. Never was that more obvious, or important, than when he tried to ‘do my bit’ to bring his country together in the fledgling days of its new democracy.

Procter passed away in his birth-town of Durban after failing to recover from heart-surgery complications. He worked assiduously there for the last five years attempting to help grow the game amongst disadvantaged communities and, late in life and to his own glorious surprise, developed a passion for girls and women’s cricket.

‘You’re never too old to change, Proccie.’ I knew him well enough for over 30 years to say that before he died. And he always agreed. He will be deeply missed, but fully, and properly, appreciated in the fullness of time.

What a privilege as a kid to be able to watch some of the greatest cricketers of all time, live at Kingsmead. For the price of a cooldrink too. Proccie; Barry; Graeme (for EP & Tvl); Ricey and so on. What memories! Proccie and Barry even played club cricket in those days, down the road at DHS Old Boys & Glenwood Old Boys. Big Vince, Proccie & Kenny Cooper- a fearsome bowling line-up.

That’s a lovely obituary to a truly great player - I was fortunate enough to have seen him play for Glocs against Surrey when I was a kid.