Jackers didn’t enjoy flying at the best of times but it was particularly grueling in mid-90s India before the airports had all been upgraded and expanded. Delays were inevitable and long and many of the Air India planes looked and felt like they’d seen better days.

In order to move their cameras and cabling around the country, the television production company on South Africa’s 1997 tour had hired their own aeroplane, a Russian transport monster retired from military service into a new life as a private mover of goods – and a few people.

In the bar one evening Jackers was having a couple of soothers and dreading the next journey to Ahmedabad, or maybe it was Kanpur, which involved two flights and a six hour stopover in Kolkata. “At least you know you’ll get there in one piece,” muttered the TV producer into his glass of Old Monk and Coke.

All that mattered to Jackers was that it was direct with a door-to-door travel time of about five hours rather than closer to 20. Some paperwork needed to be filled in and there was an issue with insurance - “I’m not going to be in a position to sue you if we don’t make it...” Jackers said.

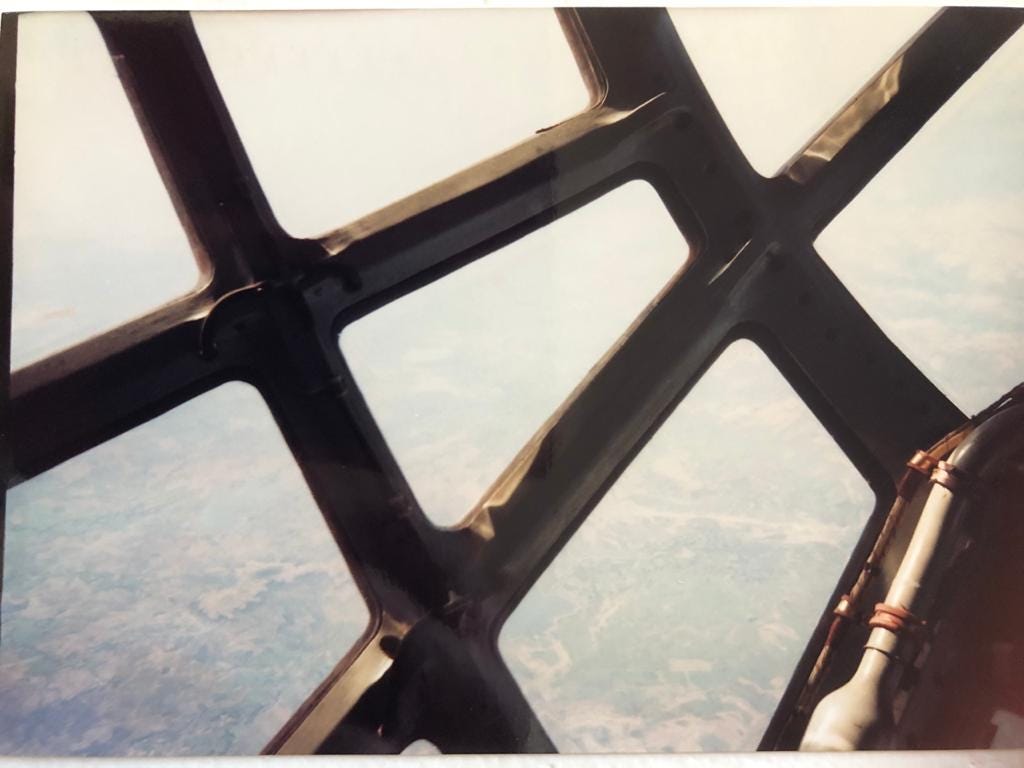

It was a beast of an aeroplane, big enough to accommodate troop carrying trucks. The Russian crew wore over-sized ear-mufflers but it wasn’t until we started taxiing to the runway that we realised why. We couldn’t hear ourselves speak, never mind our colleagues.

Taking off was a mobile earthquake. How can something so large shake and rattle so violently without falling to pieces? Only at cruising altitude did the few ‘extra’ passengers start worrying about each other. Shit - where was Jackers? He must be a wreck.

Far from it. The Fox had made himself comfortable in the navigator’s seat, a position made redundant by the installation of a radar. He couldn’t have been more comfortable with his crossword, a large bar of kit-kat and an ash-tray. Just in front of his feet were glass panels. It was terrifying. “If we go down at least I’ll be able to see what we hit, old boy.”

Flying and curry did not agree with him. Especially at breakfast when all he wanted was a plain fried egg on toast. He tried, and failed, to get one for days. The curry was already in the pan.

Having ascertained that breakfast started at 6:00am, Jackers asked the chef: “I would like the first egg you fry, please. Before you put that effing curry in there. Fry me an egg and leave it on a plate, I’ll be here at 7:00am. Please.”

The following morning, there was the egg. Cold, but curry-free. As Jackers reached for it, the young assistant chef grabbed the plate and threw the egg into the waste bin. “That old one, not good – I make you fresh one.” The air turned blue. “My effing kingdom for an effing fried egg – what does an effing man have to do to get an effing egg without effing curry on it?!”

He slumped down at his table and consoled himself with a cup of tea, again. There was silence for a minute but it was too much for the rest of the touring diners who could no longer bite their lips. A muffled chuckle, a gagged snigger – then an explosion of laughter. Jackers simmered on for a while longer but couldn’t maintain it. The corners of his mouth turned upwards and the smile was back: “At least I’ll lose a bit of weight,” he grumbled. The irony that he was born in the Punjab was never lost on him.

In Pakistan a year later he had further opportunities to lose weight, not least by having to do the pitch report in full jacket and tie: “Who the bloody hell thinks it’s a good idea to do a pitch report dressed like you’re going to church? I haven’t sweated like this since I bowled 15 overs on the trot against Middlesex in 1976.”

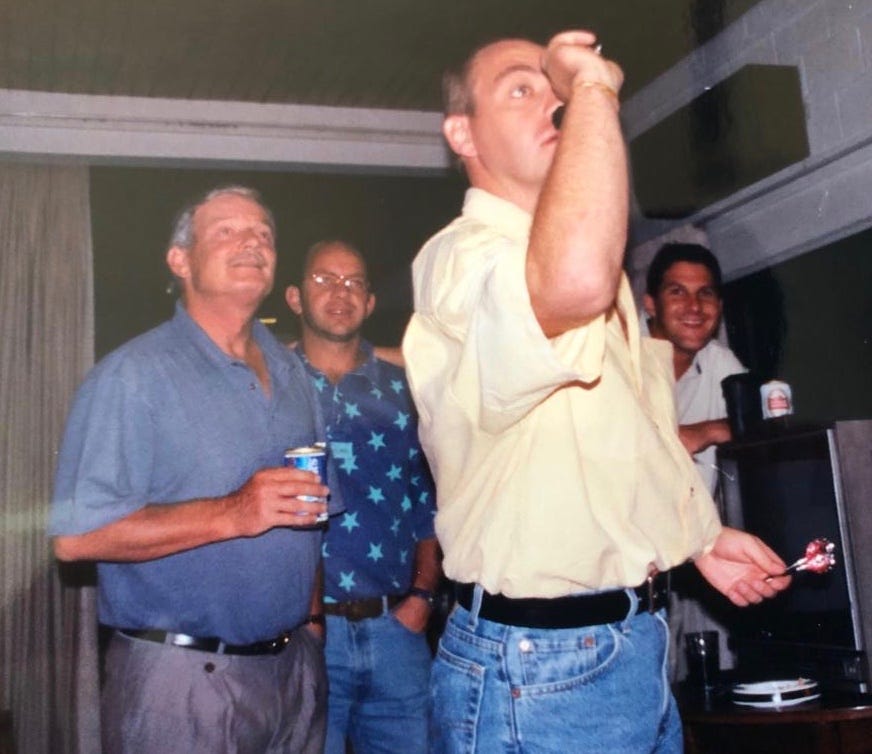

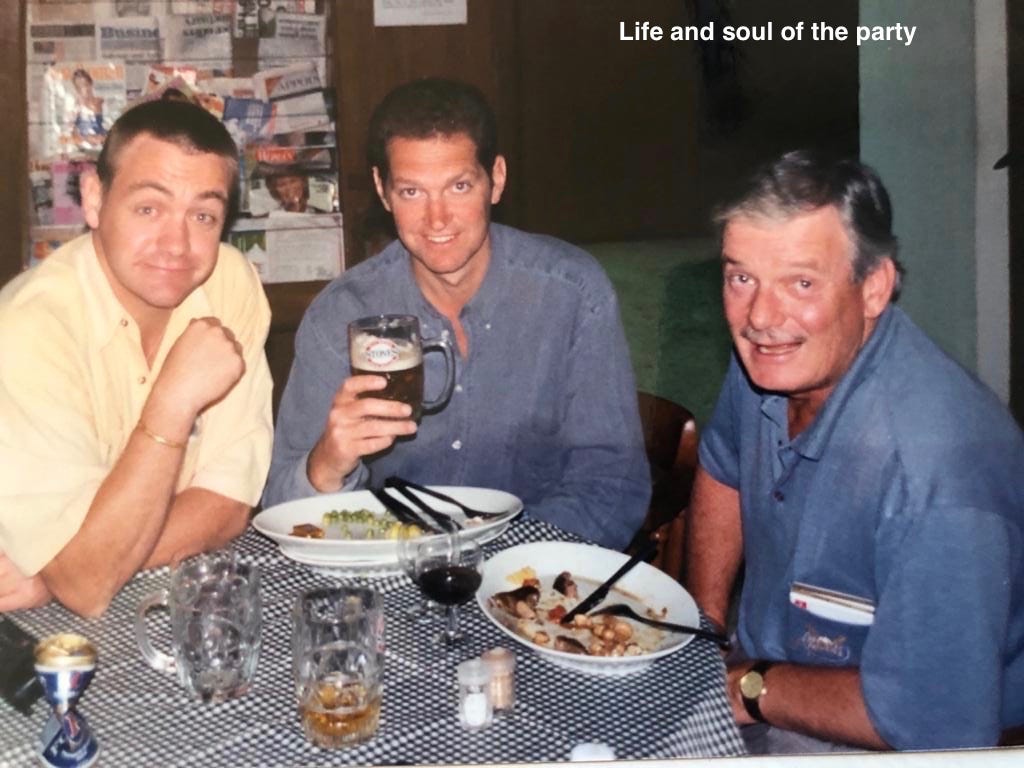

There was, at least, the haven of the ‘British Club’ in Lahore which offered very welcome cold lager and meals like fish and chips and bangers and mash. Jackers excelled, as you would expect, at both darts and pool but really came into his element when somebody mentioned that Monday was karaoke night. Nobody did a cover version of Rhinestone Cowboy like Robin David Jackman.

The obituaries I have read have been fulsome in their praise of the cricketer, the coach, the commentator and the man. Even the husband and father although Jackers was adamant that Yvonne deserved all the credit and praise for raising their two daughters while he pursued his cricket career. There is nothing I can add to that praise.

I have never written an obituary for a close friend before. A few years ago, discussing his book and the challenges of biographical writing, I mentioned that, one day, obituaries would be written about him. “Well, Manners, old boy, try and put a smile on people’s faces if you write one.”

I’ll try, Jackers.

If you enjoy my journalism, there are a couple of ways you can show your appreciation. I am entirely freelance but have no intention of going down the ‘paid subscription’ route.

You can Buy Me a Coffee. You can buy several coffees if you like (simply change the number of coffees to your preferred amount). Or, you can also donate here if you prefer not to use PayPal.

Alternatively, please encourage anyone you think may be interested to subscribe.

Of course, you are welcome to continue reading for free.

Beautifully written tribute about a wonderful man, cricket and commentator. Loved his commentary as do I miss yours on Radio 2000 Manners.

What a lovely, masterful piece - brought a touch of hayfever to my eyes. That picture of Jackers on the flight doing his crossword with his B&H by his side is priceless.