The desire to sign international ‘stars’ for domestic T20 competitions has been an amusing obsession for many years, as if it was a requirement for the tournament to even take place.

It was understandable at the beginning. Attention-seeking was important and the (same) big names appeared everywhere. It wasn’t a real league without Chris Gayle, Kieron Pollard and Dwayne Bravo. Gayle was even persuaded to play in Zimbabwe. It required a bulbous brown envelope bursting with dollars and a suite in Harare’s best hotel but he delivered with a trademark, rasping century, one of the easier of the 22 he scored in the format.

But what difference does it actually make? Not counting the IPL where the presence of the world’s best players has an obvious and mostly measurable financial effect, do all of the other leagues enjoy a financial return on the massive wages they pay for the big names? How does it work?

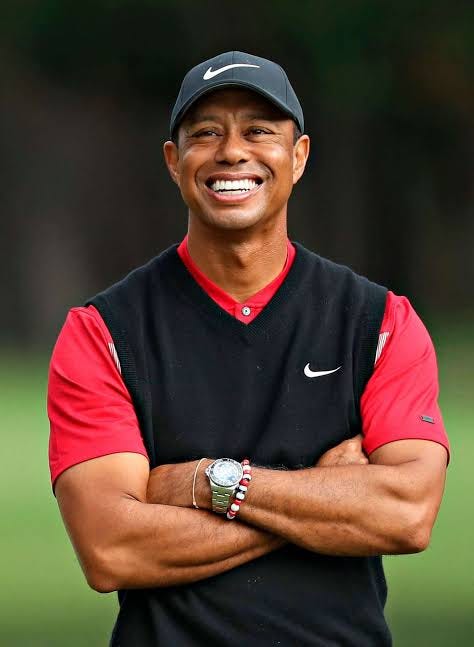

Let’s start at the very tip of the sports pyramid. Tiger Woods and Lionel Messi. Ben Stokes would scoff at the comparison, and rightly.

When Woods was in his prime the Abu Dhabi Government paid him a $2m appearance fee to turn up at their golf championship, way above the winner’s cheque. And it wasn’t just because they ‘could.’ They had worked out the difference it made in the TV audience and physical attendance. They could measure the difference between when he played and when he didn’t and could justify the fee on a spreadsheet rather than a hunch.

The scientific tracking of media coverage and the increase in global TV viewership still relies on some estimates but merchandise sales are clear-cut, as are the number of minutes a player appears on-screen. This can be controlled and even manipulated, of course. Television directors at events like these (non-majors) are routinely informed about how many minutes they are ‘up’ or ‘down’ on the required exposure of a particular player.

In Messi’s case, nobody was bothered with such fripperies as a salary. His contract with Major League Soccer (MLS) and Inter Miami includes a unique revenue-sharing agreement. As part of the deal, Messi receives a share of the Apple TV MLS Season Pass revenue. MLS has a 10-year deal with Apple TV which is reportedly worth $2.5b. Messi’s participation in the League certainly boosted viewership and subscriptions and made him wealthier than many countries.

Of course, this strategy can backfire at times. Woods missed the cut at the Abu Dhabi Golf Championship in 2013. And reportedly, many fans have sought to obtain a refund from Inter Miami when, having travelled great distances to watch him play, he didn’t make it onto the pitch.

As far as bums-on-seats are concerned, it is hard to accurately establish the additional spectators. Are more people inclined to attend a match at the MA Chidambaram Stadium when MS Dhoni is playing? Undoubtedly, but the ground is always full anyway. But Indian cricket lovers (and administrators) will tell you that ticket prices on the unregulated markets definitely increase. And in some cases that doesn’t just benefit the touts selling them.

Romantics may tell you cricket lovers in Cape Town will never forget Stokes’ 258 off 198 balls in the New Year Test of 2016, and that he will always have a ‘special’ relationship with Newlands and Capetonians. Whether that’s true or not, and whether it means another 500 of them through the turnstiles, is impossible to measure.

But the SA20 will be able to track any increase in TV audience, and specifically for MI Cape Town matches, although it will again be difficult to ascribe that to Stokes’ presence. There is definitely an up-tick in the viewing audience when Dhoni comes to the crease in India. Again, this can be measured and tracked against times when he is not at the crease.

It is difficult to establish beforehand whether Stokes' presence will lead to an increase in sponsorship and advertising. But a sponsor would be more inclined to sponsor a team with Stokes in it. So, it may be a factor in getting a hesitant sponsor over the line. And anyone in the sports business in South Africa will tell you there are more hesitant sponsors in the current market than committed ones.

Another huge bonus for the SA20 which can only be ‘measured’ in future seasons is the knock-on effect Stokes’ presence in the league will have on other players’ participation, and not just Englishmen. Stokes consulted with Jos Buttler and Liam Livingstone with whom he shares an agent, Neil Fairbrother, who also manages Joe Root. If Buttler’s time in the SA20 persuaded Stokes to sign up then Stokes could influence just about anybody.

Nobody is suggesting that Benjamin Andrew Stokes is in a similar category of superstar to the other sportsmen mentioned here but he’s somewhere near the top of the pile amongst current cricketers and may well have a winning influence on a bottom-of-the-table (twice) team and the league as a whole. But apart from all the difficulties in quantifying his influence, there’s one very good reason we’ll never actually know.

Unlike all of the mortals who are bought and paid for in a public auction, Stokes – like Buttler – is amongst the elite whose price tag remains a secret and is never published. If you don’t know how much something cost, you can’t say it wasn’t worth the money. When we’re told (and we will be, often) how great the England Test captain has been for the SA20, we’ll just have to go along with it.

(Many thanks to everybody who spoke to me for this column. And to everyone who bought me a coffee last week!)