Even modern limited overs teams have a curious relationship with ‘net run-rate’. It is spoken about privately but rarely do players or coaches acknowledge it publicly as a factor in their plans before or during a tournament.

The fear of arrogance and complacency, whether real or perceived, the centuries old respect for ‘Mother Cricket’ and a dose of old-fashioned superstition preclude any recognition of the importance of the tie-breaker until the last possible moment. Or when it’s too late. They fear it is disrespectful to the opposition.

Nobody wants to talk about winning quickly, or easily, before a contest has started. It’s not just a bad look but tempting fate and running the risk of incurring the wrath of Mother Cricket persuades teams to focus on winning “…and the rest will take care of itself.”

Using net run-rate as a tie-breaker is more likely to produce a ‘fair’ outcome over the course of a protracted tournament like the IPL which finally finished its group matches at the weekend with no less than four teams tied for fourth place and the final spot in the Play Off matches. Faf du Plessis and his Bangalore team won their final six matches comprehensively and just squeezed the others out, which seemed reasonable.

It is far from fool-proof, however, and when it is used to decide qualifiers over a much shorter span of games, the result can be badly skewed by a single, outlying result. In a tournament like the T20 World Cup starting in 12 days time, the ‘big’ teams need to do all they can to beat the smaller teams convincingly in the five-team group stages to avoid ‘chasing’ the run-rate in order to qualify for the Super Eight stage. It happened in the 2021 T20 World Cup – lest you need reminding.

South Africa, England and Australia finished level with four wins from five matches but South Africa were eliminated. A massive victory in their penultimate match against Bangladesh could have changed that. They completed the first part of the job by dismissing the Banglas for a meagre 84 with Kagiso Rabada (3-20) and Anrich Nortje (3-8) to the fore at the Sheikh Zayed Stadium in Abu Dhabi.

They needed to score the runs in 10 overs to overtake Australia’s NRR but, on a surprisingly spicy pitch the Proteas stumbled to 33-3. What was required was a ‘no-fear’ policy of attack but the fear of such an approach resulting in defeat persuaded Rassie van der Dussen that securing victory was more important than doing so in the required time frame.

Van der Dussen is a logical, pragmatic and sensible man. ‘What if we’re bowled out and don’t even win the game? What’s the point of run-rate then? And who knows what will happen when Australia play the West Indies tomorrow? Australia might lose.’ They were characteristically sensible thoughts. And also fatal.

Rassie was dismissed for 22 from 27 balls just five runs short of victory, pedestrian by any T20 standards. But he had secured victory in 13.4 overs. The following day an elderly West Indies team, already eliminated, treated their final game against Australia as a knockabout Benefit Match for Chris Gayle and Dwayne Bravo and lost, heavily, in a blaze of ignominy.

Although the Proteas thrashed England in their final match it wasn’t enough to edge out the Aussies who, of course, went on to win the tournament.

Next month’s tournament starts with four groups of five teams with the top two progressing to the Super Eight stage. It is absolutely no coincidence that England and Australia are grouped with three minnows (Namibia, Scotland and Oman) as are India and Pakistan (Ireland, Canada and the USA). The ICC cannot afford an early exit for those four nations.

Hosts West Indies have a trickier group which includes New Zealand and Afghanistan as well as Papua New Guinea and Uganda while South Africa face an equally slippery route with Sri Lanka and Bangladesh as well as their bogey team, the Netherlands. They surely won’t stumble against Nepal? It is entirely possible that each of the big three teams in the group will lose once to each other and win the other four matches, as happened three years ago.

When the net run-rate tie-breaker was first introduced it was seriously unpopular amongst players, mostly because they didn’t have a clue how it worked. And still don’t. In the 1979 Benson & Hedges Cup in England, Somerset were top of their group playing the final match against Worcestershire. They could afford to lose but a heavy loss would have eliminated them, on net-rate. (It was called ‘bowling strike rate’ back then, but never mind…)

Captain Brian Rose won the toss and chose to bat first. And declared at 2-0 after one over, effectively conceding the match but proceeding to the quarter-finals. “If they make stupid rules then they should expect people to take advantage of them,” Rose said. Somerset were subsequently thrown out of the competition and the laws of the game were changed to ban declarations in professional limited overs cricket.

I have a feeling that your hypothesis does not need statistical corroboration. It just makes sense...!

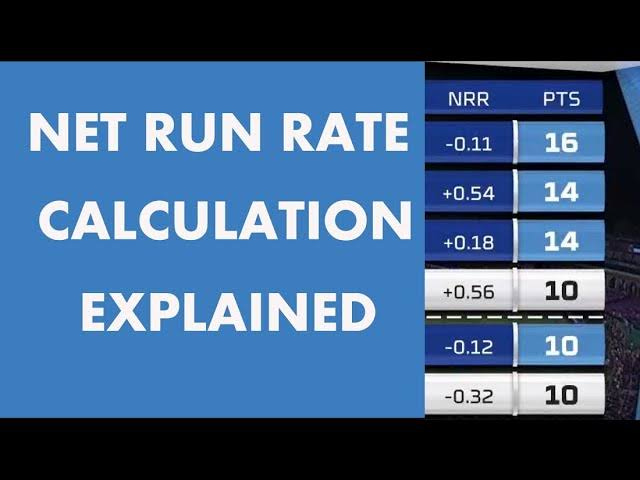

NRR is meant to give a measure of how well a team has won or lost over a series of games. Have they won handsomely? Were their losses at least close games?

The one thing that NRR does not consider when determining the 'closeness' of a game, is the wickets lost in a winning chase. It only considers the number of over taken to get to the victory.

Example: Assume 2 sides have a NRR = 0.

Side-A chases 180 and gets them 9 down in the 14th over.

That was an extremely close game, but Side-A gets a BIG NRR boost.

Side-B chases 180 and gets them 2-180 in the 19th over.

Side-B has won easily, but only gets a SMALL NRR boost

Most sides chase targets in the Side-B manner to ensure victory. I think because of this, NRR always favours the sides that bat first.

I have no statistics whatsoever to back that claim up!